Extreme. Insanity. Obsession

Sound familiar? Like words associated with fitness programs that constantly pop up on TV and on your social media feeds, perhaps?

Listen, it’s no wonder that many of us believe that working harder and eating less — or in other words, doing more — is the only way to get amazing results.

For a really long time, I took that message to heart. I wore it like a badge of honor. I exercised for several hours a day, sometimes even doing two workouts in the same day. I also followed a very strict diet that didn’t even come close to fueling the amount of work I was asking my body to do (or allow my body to properly recover from all that work!).

It was only a matter of time before I worked myself into the ground. And you know what’s worse? The results I was training so hard for only seemed to slip further and further away.

And I know this hasn’t just been my experience. I hear stories like mine all the time from women in the Girls Gone Strong community — GGS Coaching clients and fitness professionals alike.

As one client shared:

“I just figured I’m not getting results, I need to do more.

I need to run more.

I need to work out more.

I need to pay attention to what I’m eating more.

I need to stress out more.”

But here’s the thing.

There might be another way — a better way — to finally see the results you want. One where, as clichéd as it sounds, less truly is more.

In this article, I’m going to fill you in on why more isn’t always better. I’m also going to teach you how to design your training program so that it guides you toward success — and helps prevent burnout.

Before we dive in, let me make one thing clear: You get to choose how much and what type of activity you do. Your goals and what motivates you to set those goals are personal and valid.

You’re in charge.

This article is simply meant to give you more information about why people often:

- Get stuck, burn out, or struggle to reach their fitness goals, even if they’re kicking their own butt day in and day out.

- Believe that pushing themselves to the limit is what they have to do to see results and that anything less will be a wasted effort (often leading to do nothing at all and then feeling bad about it).

Let’s start by looking at why more isn’t always better.

The Many Problems With the “More Is Better” Approach

When it comes to meeting goals, particularly ones like fat loss or improved athletic performance, it’s easy to feel like you’re never doing enough.

If you’re like me, you may have had this reaction after seeing some initial results:

“Oh, it’s working! Maybe if I just do a little more, I’ll speed things up or see even better results!”

And then you add a little more time to a cardio session. Or add another set to all the exercises in your strength training workout.

Or maybe what started as doing more in the gym has come into the kitchen. You start making changes to your diet. Make your meals a little smaller here. Cut a few more calories there.

At least, that’s what I did, time and time again.

Except it never worked the way I thought it would. All it did was leave me exhausted, ravenous, and burnt out.

As tempting as it is to just keep doing more — I mean, it worked at the very beginning, why wouldn’t it work now? — instead of progressing, you may be…

- Feeling intense soreness from exercise, giving you the illusion that you’re actually working harder than you are.

- Triggering hormonal issues.

- Making yourself even more hungry, making it difficult for you to stop eating everything in sight.

- Igniting something we call appetite entitlement, which is the feeling you get that you “deserve” treats for all your hard work.

So many women in the GGS community — myself included — have learned this at the cost of our overall well-being!

I’m going to break down four problems with this “more is better” approach to help explain why it doesn’t work (and what you can do instead!).

Problem #1: Doing More Just Isn’t Sustainable

Even when you love it, hours upon hours of exercise each week can drain your schedule, your energy, your productivity, and your social life. There are only so many hours in the day, and most of us face competing demands for our time, including:

- Working or going to school — or both!

- Spending time with partners and children.

- Caring for family members.

- Doing housework and running all the errands that keep things going smoothly.

- Volunteering or being involved in different organizations.

- Participating in leisure activities that bring us joy.

By constantly trying to increase the amount of time we spend in the gym, we may hit a point where we begin neglecting other parts of our life. This means that:

- The quality of our work may suffer.

- We’re skipping social activities that we used to look forward to.

- We’re not spending as much time with our loved ones (or we’re not quite “present” when we do spend time with them).

Plus, because we’re doing so much, our bodies never get to recover fully. We reach the point where we don’t have the energy or mental clarity to engage fully in any part of our life, gym or otherwise.

As my good friend, GGS co-founder and Head Coach for our GGS Coaching program, Jen Comas recalls:

“For years, I put my life on hold. All I did was grind away, working toward fat loss. When I say it was all I did, I’m not exaggerating — my only hobbies were working out, prepping food, and dieting, all in a quest for the ‘perfect’ body. If I wasn’t working out, preparing food, or eating, I was thinking about it.

I would spend all of my free time designing or logging my workouts, planning out my grocery lists and meals, or simply daydreaming about food (mostly because I was always hungry). I avoided doing almost everything that wasn’t centered around fat loss, because I was so nervous that it would interfere with my meal and gym schedule.

Oddly, despite all of that exercise, I wasn’t getting leaner. I wasn’t getting stronger, either. I wasn’t any closer to being able to do a single unassisted pull-up or regular push-ups.

Despite not seeing the results I wanted, I had become quite obsessed about my workouts. If I had to skip a session due to an illness or some other obligation, I was instantly riddled with feelings of guilt. I was exhausted, both physically and mentally.

Finally, on a Saturday afternoon in 2013, after seeing a really fun photo that my friend had posted on social media, it suddenly hit me: My entire existence was centered around fat loss — I had turned fat loss into my sole purpose.”

This mindset can creep up on us, and it can have a profound effect on our lives.

If you’re already…

- Spending a lot of time exercising

- Consistently cutting calories or worrying about food

… but you’re still not achieving the results you want, it’s easy to fall into the trap of believing you need to do more. We’ve all heard the phrase “no pain, no gain,” after all. Do you find yourself thinking of that as you work harder?

Or maybe you’re thinking, “But I love to exercise!” If that’s the case, then great! It’s when you begin shaping your workouts and diet around the idea that you have to do more, regardless of the side effects, that it might be time to shift the script.

This is a great time to take a step back. Ask yourself the following questions:

- Can you honestly say that you’re not sacrificing any aspect of your life in order to exercise or diet?

- Do you feel like you can keep going like this forever?

If the answer to either of these is no, it’s a good indicator that you’ve fallen into the unsustainable “more is better” mindset.

Problem #2: Your Caloric Intake Begins to Work Against You

When you’re training too much or too hard, chances are you’re also doing one of these two things nutrition-wise:

- Cutting way back on your calories.

- Inadvertently overcompensating for your large energy expenditure by eating way more calories than your body needs.

Obviously, if fat loss is your goal, eating more food than you need is going to seriously hinder your results.

But did you know that eating way less than your body needs can work against you, too?

Despite this, have you ever seen an article in a fitness magazine that recommended a 1200-calorie-per-day meal plan? Or have you ever worked with a trainer who recommended both a low-carb and low-fat diet for weight loss?

If so, you’re not alone. Countless women are misled into eating far less food than they actually need to support high-intensity training.

With messages that tell women to eat as little as possible and that glorify diet culture, many women lose their sense of what “enough” food really is — especially when trying to lose weight. This altered perspective can hinder fat loss, strength gain, muscle gain, energy levels, and overall health.

The truth is that if you’re not eating enough food (particularly protein), you can experience a whole host of issues, including:

- Muscle loss, which is already a concern for women in their 30s and older. Your muscle tissue breaks down when you train, and without adequate calories and protein, it won’t be able to rebuild. Additionally, if you’re under-fueled then your body will break down your muscles and use that protein as fuel.

- Lower power output during training. You may feel like you’re training intensely, but if you can’t maximize your power when lifting, then you might struggle with muscle growth and rebuilding.

- Reduced capacity to recover from training. And proper recovery is just as important as training itself when it comes to seeing progress.

- Sleep disruptions. Evidence shows that high-quality sleep is essential for recovery after a tough workout.1 Poor sleep can also cause us to hold onto body fat.2

If you’re under-eating on a consistent basis, you can bet you won’t be performing as well in the gym or losing body fat while maintaining your muscle.

So how do you know if you’re eating too little?

Some of the most common symptoms of under-eating include:

- Low energy

- Insomnia

- Mood swings

- Brain fog or poor concentration

- Depression or anxiety

- Hair loss

- Feeling cold

- Loss of menstrual cycle

- Infertility

- Constipation

- Low sex drive

- Sugar (or other food) cravings

You may also notice that you’ve hit a ceiling on your ability to lift or that you aren’t making progress in certain areas of training anymore.

If you’re experiencing any of these symptoms regularly and you’re not sure why, then this is a good time to assess your diet to ensure you are getting adequate intake of calories and macronutrients. (Be aware that some of these symptoms can be due to other medical issues that should be treated by a physician; if these symptoms don’t rapidly improve with increased energy intake, you should consult your healthcare provider.)

If you’d like more information on under-eating and how to determine your appropriate energy intake, check out this great article by Laura Schoenfeld, RD.

Problem #3: Your Body Starts Conserving Energy and Burning Fewer Calories

When you’re training a lot and very intensely (and especially if you’re not eating enough calories to sustain that level of work), your body responds in the way it was physiologically programmed: it starts conserving energy and directing calories to functions that are necessary for survival (like breathing and regulating body temperature). In other words, your body resorts to burning fewer calories.

This worked really well when our calorie restriction was due to famine or poor crop turnout; our bodies had to step in to help us stick out the rough times. The adaptation was necessary for survival, and human bodies got really good at it — it actually increased our bodies’ efficiency. But this adaptation is not so great when we’re trying to achieve goals like fat loss or muscle gain.

When high-intensity training meets energy scarcity, it can become nearly impossible for your muscle tissues to repair after training, let alone to increase muscle strength or size.

This energy deficit can seriously weaken your power in training sessions in general. You’ll have a harder time maintaining your results and making further progress.

What’s more, when you don’t eat enough, your body:

- Reduces active thyroid hormone.

- Decreases sex hormone production.

- Raises adrenal stress hormones like cortisol.3, 4, 5, 6, 7

When your cortisol is chronically elevated, you can wind up with both leptin and insulin resistance, an unhealthy hormonal state that promotes body fat and water retention (and causes long-term health issues that go way beyond weight loss resistance).

So basically, over-exercising coupled with under-eating can lead to hormonal imbalances, and hormonal imbalances often prevent weight loss.

On top of this, evidence shows that women who exercise regularly with a chronic energy deficiency (from a lot of exercise, not enough calories, or a combination of both) may end up with:

- Functional hypothalamic amenorrhea (FHA). Amenorrhea is the loss of menstrual cycle for more than three months (or an irregular cycle for at least six months). You can learn more about amenorrhea and exercise in this article.

- Decreased energy expenditure. Evidence shows that there is a decrease in energy expenditure associated with caloric restriction. This is a metabolic adaptation in which your body naturally down-regulates your energy demands. This includes your non-exercise activity thermogenesis (i.e., calories you burn by doing anything physical that isn’t intentional exercises, like fidgeting) and resting energy expenditure (i.e., calories you burn at rest, like during sleep) so that you expend less energy throughout the day (and night!) without even realizing it. Additionally, your cells become more efficient at getting energy, which decreases how much energy you need to survive.8, 9, 10

Problem #4: Your Risk of Overuse Injury Increases

If you’re in the cycle of exercising at a high intensity on an almost-daily basis trying to get better results, then it’s almost certain that you’ve experienced:

- Soreness

- Joint pain or aches

- Tight muscles

Maybe you’ve continued pushing past these annoyances, or maybe you’ve thought that just “stretching out” the tight area would be enough, or maybe you’ve thought that more exercise was the way to “loosen it up.” Or if you’ve taken a day or two off to try and recover, maybe you’ve felt guilty about taking a break and jumped back in as soon as you could.

When we’re in this cycle of always doing more, we can sometimes get into the habit of ignoring our body’s signals.

As you’ve already learned, the combination of intense exercise and low caloric intake can cause muscle loss, lower power output during training, and reduced capacity to recover after training. This combination sets you up for injury, especially overuse injury.

Overuse injuries are typically muscle and joint injuries caused by repetitive trauma or training errors. Stress fractures, tendinitis, and shin splints are common ones. So if you’re running five miles every day and ignoring that nagging (and OK, maybe increasing) shin pain, you might be developing a problem that is compounded by muscle loss and your reduced capacity to recover after training.

Going back to that “no pain, no gain” thing. If we’re in that mindset, then it makes us more likely to look at pain as a sign that, “Hey, maybe this thing’s working. If I just push a little harder, I’ll do even better.”

Pain, though, is a signal from our brain warning us that something might be amiss. This might be a perceived threat of instability or weakness we need to keep an eye on, or it may be an indicator of actual tissue damage.

It’s super important to tune in to our bodies, especially when we’re working toward a goal. As you’ve already learned, it can be easy to fall into always wanting to push yourself to get results. Push yourself to run faster, train harder, lift heavier.

But pushing yourself too hard when you’re already dealing with the other issues we’ve talked about (like muscle loss) makes injury a much bigger risk.

Too Much of a Good Thing?

Generally, exercising consistently and eating mindfully helps us meet goals such as fat loss and strength gains. As such, we tend to see these as healthy behaviors. But excessive exercise and calorie cutting (just like excessive anything, really) can actually drag us down instead of lifting us up.

In addition to the problem with sustainability, you’ve just learned how these habits can wreak havoc on our body and our health — and in many cases these practices can move us away from our goals, which is the exact opposite of what we want!

While dedication and commitment to reaching a goal can certainly be a good thing, it’s helpful for us to take a step back and look at the big picture. Do our endeavors really contribute to us feeling better?

The foods you eat should help you feel good, not trigger guilt or hypervigilance. And exercise and movement should fill you up and add to your life, not detract from it.

So how do you break out of the “more is better” mindset and find a training and eating program that will help you achieve your goals in a sustainable, healthy way?

We gave you the link earlier to an article by Laura Schoenfeld, RD, that will help you determine how many calories (roughly) you should be eating. (Here it is again.) You also learned how to spot the signs that you might be under-eating, which may be hindering your ability to lose weight and gain muscle.

The amount of food you need will depend on…

- Physical activity level

- Stress levels

- Sleep adequacy

- History of chronic disease

- Body type

- Specific metabolism

- Age

- Sex

- Current weight

- Genetics

… and it may be higher or lower than the recommendations you’re seeing on social media, in advertisements, or elsewhere — and that’s OK. In most cases, you should avoid cutting your calories to the bare minimum. Instead, what we encourage our GGS Coaching clients to do — and what we’re encouraging you to do too! — is practice staying aware of how you’re feeling, accepting those feelings, and acting in a way that nourishes you while still moving you steadily toward your goals.

Now, we’re going to dive into how to determine what amount of exercise is right for you and your goals.

What Is the Optimal Amount of Exercise for You?

How much exercise is optimal for you will be different than how much exercise is optimal for someone else. And even how much is optimal for you may vary throughout your life — or even throughout your week!

Instead of constantly trying to do more, we encourage all of our GGS Coaching clients to figure out their own exercise “sweet spot,” or Optimal Effective Dose (OED).

Your OED exists on a continuum between your Minimal Effective Dose (MED) and your Maximum Tolerable Dose (MTD). Let’s look at each of these in turn.

In training, the Minimum Effective Dose is the minimum amount of stimulus needed to achieve a desired effect. MED is appropriate for people who want to generally improve their health, are already struggling with very high levels of chronic stress, or have very busy schedules. Think of the MED as doing the bare minimum to move forward (which can be very beneficial and appropriate for some people).

The Maximum Tolerable Dose is the highest amount of stimulus a person can handle before experiencing negative consequences. Following an MTD approach with training is for professional or competitive athletes who have plenty of time and resources to focus on optimizing their nutrition, getting plenty of rest, going for massages and other recovery care, and prioritizing sleep for the best recovery possible. Training using an MTD approach is a full-time commitment that requires time and dedication, and it also comes with the most risk for overtraining and injury.

Somewhere along the continuum between the MED and the MTD, there is a vast middle ground referred to as the Optimal Effective Dose (OED), which provides results in a relatively timely manner if you’re working hard and staying consistent while still living your life.

What Affects Your Optimal Effective Dose?

- Goals. The bigger your goals, the more you’ll likely have to train to reach them.

- Ability level. The higher your ability level, the more capacity you have to train and recover properly and the harder you can push yourself.

- Schedule. It’s only “optimal” for you if it fits your schedule. Just because your body can handle a certain amount of training doesn’t mean it’s right for you.

- Desire and commitment. Doing what you like matters. Unless it’s your full-time job or something you have to do, how often you want to train and do certain activities is important.

- Money. The more money and resources you have, the more you can invest into your recovery with soft tissue work, visits to the chiropractor or physical therapist, supplements, and so on, which may all help to optimize or speed up your recovery.

- Results. The results you’re getting will guide whether or not you’re at your OED. You can be doing everything “perfectly,” but if you’re wanting a certain result, you’ll have to pay attention to what results a certain level of training is helping you get.

- Genetics. Genetics play a role in your response to exercise, and your overall capacity to handle and recover from stress.

- Sleep. The amount of sleep you’re getting has a huge effect on your overall recovery and capacity for work and stress.

- Recovery. Recovery is not only affected by sleep, genetics, soft tissue work, and supplements but also by nutrition, stress management skills, and other recovery practices you put in place.

What Are the Benefits of Finding Your Optimal Effective Dose?

You don’t need to suffer to see results (and that goes for both exercise and eating). I realize that doing anything less than the Maximum Tolerable Dose may sound counterintuitive, but take it from me and many GGS Coaching clients who have worked at both ends of the exercise spectrum: Achieving great results is possible without going to extremes.

Whether your goal is to get lean, get strong, build some muscle, or improve your overall health and performance, following our OED approach to training will help you:

- Get a better handle on your hunger and appetite, which will help you more easily make nutrition choices that align with your goals.

- Recover appropriately between training sessions.

- Achieve your goals without compromising your physical and mental health.

- Avoid burnout.

- Expose your body to less exercise-induced stress.

- Reduce your risk of injury.

- Improve consistency, therefore also improving sustainability.

- Free up more of your precious time and mental energy.

Another major benefit of aiming for your OED is that it’s much more sustainable. Training to the max might work for a little bit, but soon enough, you may be faced with all of those negative side effects we mentioned above, like burning fewer calories and risking overuse injuries.

And wouldn’t you rather get the results you’re looking for in six months to a year versus working intensely for two months only to have your efforts stall (and even start working against you)?

Ultimately, the OED approach is about finding your sweet spot. It’s doing enough exercise to elicit the desired result within a reasonable time frame — without all of the negative side-effects that come with training more often or more intensely than necessary.

How to Find Your Optimal Effective Dose in 4 Steps

1. Get Clear on Your Goals and Priorities

Want to run a 5K, 10K, or marathon? Compete in powerlifting? Be healthy enough to play with your grandchildren? Improve your blood pressure?

What about other goals in your life? Are you working toward a degree or certification? Do you have children or aging parents who rely on you as a caretaker or a source of emotional support?

As we discussed earlier, the Optimal Effective Dose takes into account all of these factors, including (but not limited to):

- Your goals, both in terms of training and in your personal life

- Your training experience and ability level

- The amount of time you have (and want!) to devote to training

- How much money you have to invest in things like soft tissue work, nutrition coaching, etc.

- Your stress level, nutrition, sleep time and quality, and other factors that affect recovery

The Optimal Effective Dose considers your own goals, preferences, and environment, and how they all work together. In other words, the Optimal Effective Dose is realistic and sustainable.

To determine your Optimal Effective Dose, you first need to assess your goals and priorities.

Depending on your goals, your OED may require quite a bit of time and effort, or not very much at all. If you have a demanding job plus family responsibilities, your goal may be to maintain your current level of fitness or to stay healthy in general. That’s a perfectly fine goal! In this case, your OED will be very close to your Minimum Effective Dose — that is, as we covered earlier, the minimum amount of stimulus needed to achieve a desired effect.

Ultimately, it may take some soul searching to decide what’s most important to you. Is an Ironman on your bucket list? You might be willing to put your social life on hold for several months while you take the time to train for the race of a lifetime. Or you might really need to focus on your family right now — so although you’d like to improve your fitness, you’re OK with maintenance mode until life settles down a little bit.

As a part of your soul searching, think of what you’re willing to give up to reach your goal, and what you’re not willing to give up. Many people find that training for an event or working toward a big goal — such as a marathon, triathlon, or powerlifting competition — requires some tradeoffs.

You may be willing to skip Sunday brunch with your friends for a few months so that you can attend your marathon training group’s weekly long runs. Or you might decide to cut back on other parts of your household budget so you can afford a biweekly massage. In general, the bigger the goal and the more time and effort required, the more tradeoffs you’ll need to make.

Here are some questions to consider when setting and prioritizing goals:

- What are your top 3–5 goals, keeping in mind your personal goals as well as your fitness-related goals?

- Keeping in mind all of your obligations, your current level of fitness, and the resources available to you, are these goals realistic? If not, consider adjusting the goal by setting the bar a little lower or giving yourself more time to achieve it.

- What are you willing to let go so you can achieve your fitness goals? For how long?

- What are your non-negotiables? Or in other words, what are you not willing to sacrifice?

- What fills your soul and gives your life meaning? Fitness and proper nutrition should add to your life, not detract from it.

2. Identify Your Current Fitness Level

Your ability level and exercise experience will have an influence on your training plan. Naturally, more advanced athletes will be able to handle more intense and frequent training because their bodies have built up a solid muscular foundation and they’ve practiced proper movement patterns.

It’s important to realize that people at every level — beginner, intermediate, and advanced — need adequate rest. “Doing too much” is possible no matter your training background!

Identifying your level is helpful for a few reasons:

- If you’re not currently training, you can use the guidelines below as a starting point to ease back into a fitness routine.

- If the guidelines below for your fitness level differ drastically from your current routine, that’s a sign you may be doing too much (or too little) to get the results you want.

In a bit, we’ll tell you about the signs that you’re doing too much and show you how to adjust your training plan accordingly. But first, let’s look at how your ability level and exercise experience have an influence on your training plan.

You’re considered a beginner if one or more of these statements apply to you:

- You’ve started training in the last two months.

- You’ve been training consistently, but only once or twice a week at a low intensity.

- You struggle with coordination or with performing movements with good form.

- You’ve been consistently active before, but it’s been a few months since you’ve worked out more than one or two times per week.

(Note that there’s nothing wrong with being a beginner. What’s important is to determine the level that’s appropriate for you so that you can make progress and achieve your goals.)

You are at the intermediate level if:

- You’ve been strength training consistently for between two and six months, at a frequency of two or three times per week.

- You have some basic movement skills and are using moderately heavy load.

To be considered advanced means that:

- You’ve been strength training consistently for one year or more, three or four times per week.

- You have trained at high intensities and understand your needs for adequate recovery.

- You have a high level of movement skills.

As a very general rule, these classifications are pretty solid. Choose the ability level that sounds most like you. If you feel like none of these classifications feels quite right, choose the one you think most closely describes your ability level. If you’re wavering between two, choose the lower one just to be safe. You can always adjust as you go.

If you’re looking to find a healthy balance between your ability level, your schedule, and your goals, here’s a template to help.

These general guidelines are for someone who’s interested in balancing health, lifestyle, aesthetics, and performance. None of these goals take top priority; they’re all taken into account when creating a training plan, and there’s a little give and take in each category.

Keep in mind that I recommend as much low-intensity movement (like walking) as someone has the time and desire to do each week, so I’m not including it in this chart because the recommendation is always the same: move as often as you can.

Key:

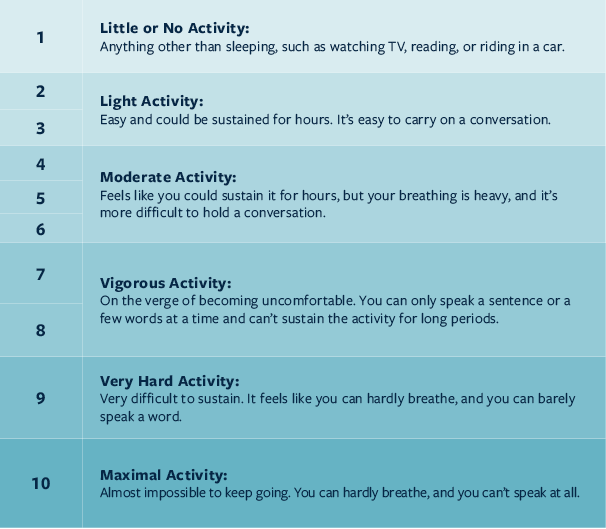

HIIT: high-intensity interval training — broadly defined as a short period of intense work performed at a 9.5–10 out of 10 on the GGS Perceived Effort Scale, followed by a period of rest, repeated for time or for a number of sets.

HIT: high-intensity training — otherwise known as vigorous-intensity cardio and defined as activity performed at a 7–8.5 out of 10 on the GGS Perceived Effort Scale. Some examples include hiking, rowing, jogging, and cycling.

MIC: moderate-intensity cardio — can be hiking, biking, swimming, fast-paced yoga, or circuit training. This is about a level 4–6 on the GGS Perceived Effort Scale.

Your current routine may be very different than these guidelines, which is OK. However, if you’re working out significantly more than this template recommends, it’s a sign that you may be doing too much. Don’t feel like you have to overhaul your workout plan just yet! Below, we’ll cover how to adjust your plan depending on how you’re feeling and your results.

Before you make any changes to your current routine, however, let’s discuss another important aspect of training: consistency.

3. Be Consistent With Your Training, Nutrition, and Recovery

If you’ve been training consistently and not seeing the results you want, your first impulse might be to adjust your training program. Maybe you start toying with trying out longer cardio sessions, adding an extra day of strength training, or starting a group class on top of your individual workouts… but not so fast! You might not need to tinker with that aspect of things just yet.

Consistency with all of the other things that affect fitness and health, like sleep, stress management, and nutrition, can be just as important (if not more so!) as your workouts, which is why we focus on all of these aspects with our GGS Coaching clients.

To make progress, you need to be consistently addressing all of the elements that work together to produce results:

- Nutrition

- Exercise (resistance training, cardio, and conditioning)

- Non-exercise physical activity

- Rest and recovery

- Sleep and stress management

If you’re not seeing the results you want, ask yourself: Have I been consistent with every part of my plan, including nutrition and recovery? Have I been…

- Practicing basic good nutrition habits, such as eating protein with every meal, in at least 80 percent of my meals and snacks?

- Eating the recommended portion sizes for protein, carbohydrates, fat, and vegetables in at least 80 percent of my meals and snacks?

- Getting plenty of non-exercise physical activity?

- Practicing stress management techniques?

- Getting at least seven hours of high-quality sleep each night?

- Sticking to my nutrition goals on the weekends?

If you answered “no” to any of these questions, spend some time focusing on those areas for the next two to three weeks, then re-evaluate your progress.

Remember, each element affects the others, and to get the best results possible it’s critical to address all of these areas. If one or more of them are suffering, that’s probably what’s hindering your progress.

4. Adjust Accordingly

If you’ve been following the same routine for four weeks, you should have enough information to know if you need to scale back or if you’re ready to amp it up.

Here’s a good rule of thumb if you’re being consistent with your eating and exercise but not making progress:

- If you’re not making progress and you feel well-rested and energetic, then do more. But don’t go wild with “more” — ease into it.

- If you’re not making progress and you feel lethargic, unmotivated, and exhausted (when you normally enjoy exercise) then either do less exercise or get more rest.

For the purposes of this article, let’s focus on the latter situation, where your body’s signals are telling you that you may be doing too much.

Here are three different options for doing less that you can choose from based on how you’re feeling and on how drastic of a change you might need to make (or would be willing to make).

Option 1: You can try doing just a little less when…

You’re not seeing results and:

- You’re feeling a little more tired than normal.

- You’re a bit less excited about going to the gym.

- You’re really worried about cutting back too much.

In this case, you might not need to make drastic changes. Here are some ways you can do a little less and recover more:

- Remove a set from every exercise in your workout.

- Remove one or two exercises from your workout.

- Reduce the weight you’re using by 10–20%.

- Rest longer between sets.

- Get more sleep.

Pay attention to how these changes make you feel. Do you have more energy during your workouts or throughout the day? Are you looking forward to your workouts again? If so, that small change may be all you need to reach your Optimum Effective Dose.

You can also try these smaller changes if you’re nervous about cutting back too drastically. If you’re used to doing a lot of exercise or watching your nutrition very closely, it can be scary to suddenly start eating a lot more or working out less often. You may be worried about going too far and losing progress on a goal that means a lot to you. If this sounds like you, it’s OK to start by doing a little less and see how you feel.

Option 2: You should consider cutting back even more when…

You’re not seeing results and:

- You’re way more exhausted than normal.

- You’re not excited about going to the gym.

- Your muscles are more sore than usual after workouts, or the soreness sticks around longer.

- Your appetite has changed a lot recently — either you’re much hungrier than normal, or much less hungry.

In this case, I recommend increasing your rest by swapping out a regular workout for an active recovery day or a less-intense form of that type of exercise at least once per week. For example, you could:

- Take a yoga or Pilates class (beginner to intermediate intensity) instead of strength training one day per week.

- Go for a restorative walk instead of doing a HIIT session.

- Choose a leisure activity like light hiking, biking, or playing outside with your kids or dog instead of a more intense session.

Take note of how you’re feeling after your recovery session, both mentally and physically. You might feel great that you took some time for yourself to rest and nourish your body, or you might feel a little anxious about scaling back a bit. Both of these reactions are normal! Keep in mind that changes may not happen immediately. Stick with it and reassess after 3–5 weeks.

Ideally over time you’ll notice:

- You feel more rested and have more energy overall.

- Your muscles aren’t as sore.

- You’re more excited about your upcoming workout, or more motivated to get going.

- Your appetite is more consistent.

Option 3: You may need to really cut back when…

You’re not seeing results and:

- You’re constantly exhausted.

- Your muscles almost always feel sore.

- You’re irritable or anxious (or more anxious than usual).

- You’re not sleeping well.

- You have big fluctuations in your appetite or cravings.

- You rely on caffeine to get through the day.

- You don’t want to do anything else outside of the gym, like go out with your friends or do any of the hobbies you normally enjoy.

In this situation, I would recommend dropping down a level (from advanced to intermediate, or from intermediate to beginner) in terms of your overall exercise volume and frequency. Reference the chart above for some general guidelines on what a balanced program should look like at each ability level.

Another option would be to take a full week off of intense exercise. Only do walking and gentle mobility exercises, such as stretching, easy foam rolling, or a gentle yoga class. If you feel anxious about taking an entire week off, consider timing it with another life event that makes sense — like a leisurely vacation, your holiday break, or the week your sister is coming up to visit.

In Conclusion

I want to say it once more: You don’t need to suffer or go to extremes to achieve great results (and that goes for both exercise and eating).

If you’re still thinking, “I’m not sure about this, I’m worried that doing less will just stall my results….” that’s understandable. It can certainly seem counterintuitive that doing less can actually give you better results, and it’s a concept that some of our GGS Coaching clients struggle with at the beginning too.

But the consequences of continuing to do too much can be pretty big: exhaustion, hormonal issues, an out-of-whack appetite, and overuse injuries. If you recognize the symptoms of doing “too much” that I outlined above, but you’re still a little worried, I challenge you to do two things:

- Be more consistent with your nutrition and recovery.

- Try doing a little less — whatever you’re comfortable with from the options I outlined above — and see how you feel after a few weeks.

I’ve seen so many women in the GGS community feel better and get better results when they embrace the OED approach. Going hard, hard, hard, just isn’t sustainable (unless you’re an elite athlete with plenty of time and money to devote to training, nutrition, and recovery). And for many of us, it isn’t very fun!

As I said earlier, fitness should add to your life, not detract from it.

By rethinking the “more is better” approach, you can have a more balanced life and achieve better results.